July 25, 2005

Other Publications

I published a longer piece about Turks in Germany here. Check it out.June 23, 2005

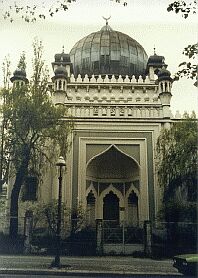

Wilmersdorfer Moschee/ Wilmersdorf Mosque

At a conference at the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees entitled: “Islam and Integration,” the typical problems of whether Turkish culture or the Islamic faith was at fault and other such unanswerable academic questions were continually raised. One panellist, in an attempt to show the positive sides of integration, started by giving an historic overview of Islam in Germany. She showed a picture of the Wilmersdorf Mosque, which was built in Berlin between 1924 and 1928. The Wilmersdorf Mosque represents any student of culture’s dream project because one can see the transformation as well as the strife over a religious symbol.

The Mosque, built in the Moghul style by the German architect K.A. Hermann, was financed by the Ahmadiyya Anjuman religious community from Lahore, Pakistan to carry out missionary work in Germany and serve the small (cerca 1000) Muslim community living in Berlin. The Mosque was badly damaged during the war as the German troops had used the Minarets to fire on the Russians. However, after the war the Mosque was reconstructed by the British authorities.

Another panellist from Berlin reminded the earlier panellist that the Mosque had more of a modern history as well. In the 1970's Siemens made a postcard out of the mosque to send to Turkey. This postcard was supposed to show how Muslim friendly Germany was and encourage Turkish guest-workers to move to Germany to help supply able bodies for the post-war German industrial machine.

Many Germans and those from the west now see the mosque as a sign of danger. It’s funny how times change. Can anyone now imagine a western company using a mosque to attract laborers?

June 6, 2005

Ein Druck/ A Push

The buzzword is integration. Turks, Germans complain, speak German with a terrible accent in the third generation. They have their own lawyers, travel agents, and kabob stands. They have created a real parallel society. This is, of course a problem not only for old-fashioned reasons of national pride. The lack of German language knowledge prevents foreigners from getting good jobs. The unemployment rate is twice as high for foreign citizens in Germany as it is for Germans. The problem is further compounded by the German attachment to the social welfare state. The social welfare state, however, doles out millions of Euros to the families of the unemployed Turkish guest-workers who remain in Germany. Whatever inherent racial prejudices might exist, are exacerbated by economic ills, making for a highly combustible situation.For years, however, the Turks were told that they were supposed to go home. They were not granted citizenship and very little incentive existed for them to invest in Germany. All of a sudden Germany as done a hundred and eighty degree turn. Immigrants can now stay, but they must swiftly integrate. Forced integration, however, does not have good historical precedents. Germany’s last experience with such integration surely did not behoove the Jews.

The question of Islam, underlies this question of integration. The most outspoken promoter of forced integration, Ayaan Hirst Ali, is a former Muslim herself. However, the average secular lay Turk think the program is crazy. Many Americans who have immigrant relatives know that teaching a sixty-five year old grandmother English is an unrewarding task, especially when this grandmother has very little formal education. In Germany however Mutti muss Deutsch lernen. The new immigration law demands 650 hours of German language education.

What is more worrying is not that Mutti has not learned Deutsch, but that Mutti’s children rarely if ever go to university and only attend the most basic school. Perhaps this is similar to the problem of Latinos in the United States. However, the German school system exacerbates the problem. At the tender age of eleven, students are either sent to Gymnasium, which feeds students into university, Realschule, which gives students more advanced training or Hauptschule, the lowers level of schooling. Though possible, it is very hard to change paths so that your ability to attain a good paying job if it is determined by your teacher that you should go to Hauptschule, is extremely low. This, indeed, is where many of the gastarbeiter children end up. The push, then, needs to come in elementary education, not to make grandmas learn German.

The counter argument of course, is that parents influence their children, and therefore the parents must learn German. What is important, however, is parent’s general outlook towards education, not the knowledge of one specific language. This knowledge seems to be held by very few in Germany. Today I had a meeting with a German of Turkish origin who has started a ground-breaking program here for older Muslim women to integrate through sports and learning. She realizes the true problem but most in the German government do not.

Parents needs to support the kids, but the language barrier, as generations of immigrants in the United States has shown, is not the problem. How else can one explain the Chinese dry cleaners down the street from me who hardly speak a word of English and sent their daughter to Dartmouth.

May 24, 2005

Herr Michna

At the beginning of his class, Herr Michna makes it clear that it was a big mistake on Germany’s part to bring so many (gastarbeiter) guestworkers from Turkey, and the question now is how to best fix the mistake. Michna begins by showing his students pictures of radical Islam from the front pages of several popular German magazines and newspapers. He mentions September 11th and the recent death of Theo Van Gogh. The problem of immigrants as Herr Michna frames it is existential in nature: either integrate the immigrants in society or face death by radical Islam.An employee with the Social Ministry of the State of Hessen, with the confusingly German title of Leiter des Referats Zuwanderungs Politik und Landesauslanderbeauftrager, Herr Micha picked me up from my office to attend his university class on German immigration politics he teaches for future state employees. Fortyish, with a receding hairline, although without a hint of grey in his hair, Herr Michna plays the part of the typical German Beamte, or state civil service employee.

Driving between the sleepy state capital of Wiesbaden and its largest city, Frankurt am Main, I began to discuss with Herr Michna, the comparative problem that we have in the United States. Conservative estimates believe that eight million illegal immigrants reside in the United States, mainly from Mexico. Herr Michna quickly retorted that the Mexicans are Catholic; the Turks, Michna continued, are Muslims. Furthermore, the Turks in Germany are not the educated elites from Ankara of Istanbul but come from the Anatolian Plain, a place that has not taken on the trappings of modernity and remains a cultural backwater. Michna explained that he had visited the Anatolian plain and witnessed life there firsthand. He could not believe that Turkey was going to join the EU.

In the 1960s and 70s the Germans brought millions of Turks to work in Germany to fuel their growing economy. Many of these Turks chose to say and the German courts have made it virtually impossible to deport them. The Turkish population, however, suffers from 20% unemployment, double the already high national average and lacks many of the qualifications necessary to obtain highly-skilled jobs. In fact, Germans claim that the Turks are moving in the other direction, renouncing the Germans ways in order to create what they term parallelgesellschaft,” or parallel society. Germans continually say that the problem in Germany is that you see third and fourth generation immigrants of Turkish descent still speaking Turkish on the street, something you only see in the most sealed off of American communities such as the ultra-orthodox Jews and the Amish.

Three recent threads have recently animated the immigration debate in Germany (which mainly means Turkish debate) and brought it to center stage. First, September 11th and the recent death of Theo van Gogh, has brought the presence of militant Islam to the attention of German authorities, and they have become acutely aware of the religious difference between themselves and their immigrant populations. Second, in 2004, the Bundesrat, passed a revolutionary law that allowed for jus soli. Jus soli allows for citizenship to be based on place of birth rather than on blood, and this new law has allowed for many Turkish guestworkers to apply for German citizenship. The price of allowing these Turks citizenship, however, also included a much more proactive stance towards integration on the part of the government, which increased the burdens on those with what Germans call a “migration background”, prospective citizens including 650 hours of language instruction Third, there has been a spate of honor killings that has outraged a German public, which feels that Islam is oppressing women and not allowing them the freedom of choice.

Seventeen university students file into the classroom. They looked similar to a group of students attending state university in the US. Most of them appear in their late teens or early twenties with the necessary tattoos and piercings. Judging from their names and accents, however, none of is of other than German origin. This is an interesting fact given that more than 50% of those that live in Frankfurt have immigrated their within the last several decades and do not speak German as their first language.

In typical German style, this three hour class has been whittled down to 45 minutes because Herr Michna must attend a conference. However, this week Herr Michna wishes to leave his students with one important fact: the third generation is the most important. In his trip across the United States, he claims that officials continually told in the third generation it’s, “Princeton or prison, Yale or jail.” What the Germans want of the Turks, however, remains unclear.

May 20, 2005

New Direction/ Neue Richtung

My life has changed quite a bit since I last wrote on this blog. I am now in graduate school and am spending the summer working in the Interior Ministry of the German state of Hessen in immigration politics.Since I am no longer a boring graduate student, at least for a little while, I have decided to rekindle the blog to write about German immigration politics—a topic, which I hope you will find interesting.

August 20, 2004

Turbaza/Турбаза

Roughly halfway in between Tver and Klin the Volga River meets the Shosha river, and it is there that I spent the last couple of days relaxing in one of European Russia’s most beautiful sposts. I stayed in what is called a turbaza, a relic of the Soviet past that is very quickly dying out. In fact, my rich friend was at first shocked that I knew the word. He was even more shocked when I told him that they still existed.I didn’t actually do much at the turbaza. My attempt to learn the favorite Russian pastime of mushroom picking was thwarted by the lack of mushrooms; my Russian friends and I only managed to find a small number of the poisonous kind. However, I gained a healthy respect for the rural skills Muscovites still retain. One of my friends, an elegant language student, seemed to leap at the opportunity to catch newts in her hand and thought nothing of poking around anthills. Both of my friends could easily identify at least 15 varieties of mushrooms though they had lived their whole lives in the city.

The clientele at the turbaza were mainly manual laborers and were staying at the turbaza to fish. The place was full of nostalgia. The men wore the large Soviet plastic frame glasses and the women donned shapeless flower print dresses no longer in vogue in Moscow. The summer-camp atmosphere made me appreciate the best in the socialist ideology. The turbaza is simple, pleasurable relaxation that everyone, no matter their wealth, can enjoy.

Almost everyone seemed to know each other, and the atmosphere was pleasant. Though the beds were olds and soft, the cabins were clean and rustically cozy and pleasant to look at like unlike the pre-fab housing in Moscow. The food was also simple Russian fare. Everyone ate together in a camp-style dining hall, and the lights were turned out after half and hour, so there was now lingering.

This type of vacation as been replaced for the capitalist all-inclusive Turkish holiday. 500 dollars for a week at a five star hotel just isn’t the same, and I hope that at least a few these turbaza remain open. If they could just improve the toilets at the turbaze a little bit, I think they could eventually thrive.

August 15, 2004

Clockwork Orange/Заводной апельсин

I just recently read Clockwork Orange. I know, I know, I am behind the times and I should have read it ages ago, but I am glad that I waited.I am happy I put reading Burgess off because, having learned some Russian, it was with a strange sense of displacement that I encountered Burgess's slang. Some of the words like korova (cow) immediately popped out at me as being Russian while others, because of Burgess's strange transliteration and my own lack of knowledge seemed nonsensical at first. Yet, on a deeper level, the word play was excellent or should I say horrorshow.

The strangest sense of displacenment came today when I was having a cup of tea with my friend in a trendy cafe with lots of books on shelves (you know the type). I picked up a copy of the Russian translation of Clockwork, whose Russian title doesn't fully translate the Cockney slang of the title and sounds rather like Factory Orange, or to put it another way an orange from a factory.

"How might one deal with the problem of translating Burgess's slang of "Slavic orgin" back into Russian?" I asked myself. As I started reading the Russian copy, I realized to my amazement that the words had been left in their English language original so that after a series of Cyrillic words you would get Burgess's slang written with Latin characters. So you would get a sentence like "у него выло nozh." Crazy!

August 9, 2004

Privacy/Сфера личной жизни

While whizzing around town in Russia's versions of cabs (any driver that stops to pick you up), I have often wondered about the personality differences between Russian drivers and the more common Georgian, Armenian, Chechen, or Azerbaijani driver you get. Even though I speak Russian with a strange accent, and often try ot make some passing conversation with the Russian cab drivers, they usually remain silent. The Caucausians on the other hand, are usually full of smiles and questions.In my pursuit to learn Russian, the taciturn nature of Russian drivers has always been a bit off-putting. Recently, however a friend of mine set me right. Russians, he said, are merely being polite and are maintaining your right to privacy. It is uneducated for a Russian to be nosy about where you are from and where you are going.

This right to personal privacy is one that I think is laudable will perhaps aid Russia in its pursuit of a democratic society (though on the other hand it could just reinforce opaque government), so now don't mind whizzing around Moscow in silece. Nevertheless, I also like chilling with the Caucausians sometimes.

July 26, 2004

To Far Land We Go, My Friends/Едем мы друзя в далне край

During Krushchev’s time, after all of Stalin’s deportations of prisoners, political and otherwise, to desolate outposts of the USSR, there was another less oppressive wave of migration. This second wave of Soviet population movement was initiated as part of Krushchev’s back to the land (or perhaps to the land) movement, which aimed to settle vast stretches of the Soviet interior and open them up for agricultural production.A piece in the Context section of the Moscow Times prompted me to go see the exhibit named after a popular folk song (which is the title of this post) of the time held at the Russian State Archives (formerly the Communist State Archive). This exhibit details the history of the Komsomol (Communist Youth League) settlers who went out to work the land in these sparsely populated but agriculturally exploitable regions in what was then Kazakhstan SSR and other nearby regions. The Moscow Times noted that while traditionally this settlement had been celebrated in the Soviet curriculum, many of the documents now put another face on the experiment.

The exhibit was well laid out with photographs, paintings and hundreds of official pieces of communication from the era. Though there were dark spots, notably some people were forced to go, in this immigration in which 350,000 people participated in the first year, what struck me was the general ideological exuberance with which the young Komsomols set out on their mission. In fact, in the first years the mission was a large success in many ways because of the tremendous efforts that these young people exerted despite the conditions they lived under. There are photographs of the primitive canvas tents under whose roof many of these settlers at first lived—even through the brutal winter.

What was newly released to the public and was fascinating to read, were all the official documents that illuminated the disaster that was Soviet central planning. Many of the newly released documents show how the workers in Kazakhstan were continually promised expertise and tools that they were never given. Much correspondence dealt with the fact that a certain number of tractor operators had been promised in the wave of new settlers, and, as usual, the real number of tractor drivers was a small percentage of those promised. Supply requests were also not met, and you could almost see through the official Communist party language, the frustration felt by the people on the ground in Kazakhstan.

On the other hand, the exhibit also shows the public face of the campaign. On display are a number of pictures of Communist Party bosses enveloped in the fields of wheat as well as Soviet realist watercolors of young men and women piling hay into truck. These were the images that were shown to the masses back home and which represented the regimes success.

The shortcuts that were taken at the outset in order to boost production also led to serious long-term problems. In many of the later documents and photographs the devastation of erosion were shown. Because of the lack of proper agricultural techniques thousands of tons of topsoil blew away in the steppe winds. In addition, the harsh climate also often got the best of the settlers. One official communication explains how, because of frost and snow, only 8 percent of the crop was harvested. Pictures of tractors plowing through fields with over a foot of snow on them elucidate this quite well.

For me, this campaign is interesting to compare on several fronts. I have been meaning to read David Laitin's book about the 25 million Russians who live in the near abroad and make up one of the world’s largest diasporas. I wonder how Kazakh’s current perception of the Russian population in Kazakhstan is influenced by the original reason why much of this population came to Kazakhstan. I also wonder how Russians thing of the land they moved to in order to great the Soviet bread basket. Another interesting point of comparison would to compare the Soviet back to the land movement with other such movements such as the kibbutz movement in Israel as well as the back to land movement in the west of the United States. Any comments of these issues would be most appreciated.

July 22, 2004

Beggars and Pets/Попрошайки и домашнее животное

Russians are real animal lovers, and, as the interpreter Michael Berdy recently noted in the Moscow times, it is strange that Russians don't have a word for pets in their language (they have to use домашнее животное domashneye zhivotnoye which literally means house animal). Russian's care for animals can be seen in the love they give both to their own pets and mangy looking street dogs.I see my neighbors stoop to both feed and pet the poor mongrels who congregate outside my metro stop. I wouldn't go near these animals, let alone touch them, but Russians are obviously very fond of these dogs. Recently, though, I have begun to wonder whether Russians have more sympathy for homeless animals than they do about dogs.

Throughouh the Moscow, like throughout U.S. cities homeless people are seen with animals in tow. The signs that these people in Moscow show, however, are different. With almost no exception, the homeless people's signs in Moscow say "Please help my to feed my dog" or "Help my feed my kittens or buy them." This, I think, is different to in the U.S. where dogs might arouse sympathy, but people's sign don't specifically mention the dog and not mention the person begging.

Homeless people are not stupid, and they must have realized where people's sympathies lie. Clearly if they say "homeless and hungry," they won't get money, whereas if they say "my dog is hungry people," will flip some change their way. Perhaps this has to do with Muscovites skepticism about homeless people. My students always say they are in gangs or they are really rich. Dogs, on the other hand can't have some of our more vile human impulses.